Benjamin Hampel1, 2, Cate Esson3, Bernard Surial4, Lukas Baumann4, Florian, Vock5, Jan Fehr 1 *

HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a method for people with a temporarily high HIV risk to protect themselves against an HIV infection by taking antiretroviral medication. The new following recommendations were developed within the SwissPrEPared program, which is supported by the Federal office of public health (FOPH), and approved by the Federal Commission for Issues relating to Sexually Transmitted Infections (FCSTI) on 28. August 2025.

These recommendations were developed as part of the SwissPrEPared program to assist health care professionals in prescribing PrEP. They will be adapted regularly, based on growing scientific knowledge and on quality assessment from the SwissPrEPared program and published on the SwissPrEPared webpage (www.swissprepared.ch). These recommendations are intended to inform all health care professionals who prescribe or request information about PrEP. The following recommendations are built on previously published recommendations by the Federal Commission for Sexual Health (FCSH) (1) and based on the results of the SwissPrEPared study and other international study results and recommendations (2)(3). Physicians can also join the national PrEP program, SwissPrEPared, and benefit from specific training and other support. At the date of this version (2025) PrEP is only reimbursed by the compulsory health insurances for people who receive PrEP prescriptions at one of the SwissPrEPared centers. For further information please contact the study team via www.swissprepared.ch.

Statement on Gender inclusion

The results in the effectiveness of oral PrEP are different in cisgender men and women. Some populations, such as transgender men and women remain still understudied. In these recommendations we have included the current knowledge including all gender identities as best as possible. We are aware however that our recommendations lack the inclusion of people who identify as nonbinary. This is not because we do not acknowledge their gender identities. We strongly believe that moving beyond a binary understanding of gender is a significant advancement for all humanity. However, since few studies have addressed issues related to nonbinary identity, and to make the recommendations more readable, we decided to avoid specifical mentioning of nonbinary individuals in the text. We currently believe that including nonbinary people within groups which have equivalent risk due to their genital anatomy and sexual network without always naming them makes these recommendations more accessible for PrEP prescribers. For example, a non-binary person who was assigned male at birth and is having sex with men is most likely best represented in the epidemiological group of men who have sex with men (MSM). A nonbinary person who was assigned female at birth, with masculine sexual characteristics, who is having sex with other MSM, is also best represented in the MSM group due to their sexual network risk. As this is an ongoing process in our society, we will reassess this approach with every update of these recommendations.

Large trials have shown high efficacy of the combination of Tenofovir disoproxil (TDF) and Emtricitabine (FTC) used as PrEP among several risk groups. Efficacy has been shown to be highest among MSM. Both, daily and event-driven regimes showed an 86% efficacy to protect against HIV (4)(5). Efficacy among those who show good adherence is even higher and estimated around 99%(6). Although in a 2015 meta-analysis no difference in the efficacy of TDF/FTC was seen between sexes, many studies showed a reduced efficacy among cisgender women (7). Most studies suggest that for cisgender women adherence seems to be more important than among MSM, and a longer PrEP initiation time is needed to reach steady-state concentrations in the female genital tract tissue (8)(9)(10). However, due to overall low adherence in RCTs among cisgender women, only one randomized clinical trial (RCT) demonstrated clinical effectiveness in cisgender women.(11) As a result, modeling studies using the data of these RCTs and making assumptions on the need of higher adherence for cisgender women show overall wide confidence intervals and therefore need to be evaluated critically. Alternative studies and re-evaluation of previous pharmacokinetic (PK) studies contradict these findings and suggest that the same adherence and initiation time is needed for cisgender women as for cisgender men(12)(8). Whilst clinical studies are missing to proof this new approach, new substances for the use of PrEP show promising results. Long-acting injectable cabotegravir or lenacapavir showed a better effectiveness than TDF/FTC among cisgender women but is so far not approved for prevention in Switzerland (13)(14). Moreover, its high cost is an additional barrier for an off-label use. Of note, both trials showed that low adherence on oral PrEP was again the main driver of the reduced effectiveness in cisgender women, but not medical failure.

Only few data on PrEP exist for transgender men and women (15). Therefore, for both groups, the regime for cisgender women should be used. PrEP has also shown efficacy against HIV infection through needle-sharing among people who inject drugs, with a reduction of 49% in HIV incidence (16). However, for this study Tenofovir was used as a single drug and not in combination with Emtricitabine.

PrEP is recommended in Switzerland to be prescribed to persons at substantial risk of HIV since 2016 (1). Since 2020, TDF/FTC has been approved by Swissmedic for the use of PrEP. As from 1st July 2024, PrEP is covered by the compulsory health insurance if prescribers participate in the SwissPrEPared program and in accordance with the FOPH reference document “Präexpositionsprophylaxe gegen HIV (HIV-PrEP)” dating from 31 March 2024 (17). As people who use PrEP without medical supervision potentially expose themselves and others to avoidable health risks, these recommendations aim to assure a high quality of care for people requesting PrEP, as well as encouraging physicians to offer medical supervision for people who are interested in taking PrEP.

3.1. Health care providers’ role in the PrEP prescribing process

The final decision about taking PrEP is always made by the individual based on shared decision making with the prescribing physician. In 2015, the WHO recommended PrEP for populations whose annual HIV incidence was at least 3%(18). As this approach resulted in the refusal to prescribe PrEP to people at risk of HIV but who did not meet this threshold, the latest WHO update recommends that all individuals requesting PrEP should be given priority to be offered PrEP since the request itself may indicate a higher likelihood of acquiring HIV. (19). In Switzerland, efforts to reach populations with the highest risk for HIV, mainly subgroups of MSM and transgender individuals who have sex with men must continue, as we still do not see a sufficient decrease in HIV diagnoses in these populations (20). On the other hand, to reach the 2030 goals in ending HIV transmission, more efforts are needed to reach other populations with risk of HIV exposure who might also benefit from PrEP. Individual risk might be contextual: for instance, individuals not considered at risk in Switzerland may have a higher risk when travelling abroad; alternatively, behavior may change over time and those not benefitting from PrEP at first may benefit later in the future. PrEP is often only needed for a certain period in life. This period can vary between a few days or years from person to person. Using PrEP as HIV prophylaxis is a personal and highly individual decision. Persons asking for PrEP are therefore in the best position to estimate their own risk. Together with health care professionals and provided information, they can establish the optimal prevention approach in a process of decision-making. Health care professionals should be capable to facilitate this decision-making process, provide easy-to-understand information, rule out contraindications for PrEP, and assess the existence of other medical conditions (such as anxiety disorders), since these could affect the decision-making process and adherence. Individuals who might benefit from PrEP, individuals who do not need PrEP and contraindications for PrEP are listed in Table 1.

3.2. Whom to recommend PrEP

Despite the importance of self-determination in the decision-making process for or against PrEP, certain persons deserve special attention as they are at a higher risk of acquiring HIV-infection and should therefore be informed and offered PrEP during medical consultations. Individuals who benefit the most from PrEP are listed in Table 1:

Table 1: whom to recommend PrEP and contraindications for TDF/FTC as PrEP

| Individuals who may benefit from PrEP | Individuals from groups with a high prevalence of HIV in Switzerland:

|

| AND show at least one of the following criteria: | |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

Individuals from groups with a low prevalence of HIV in Switzerland:

| |

| BUT show at least one of the following criteria: | |

Cave! For this group, PrEP is not reimbursed by the compulsory health insurance. | |

| |

| |

| Individuals who do not need PrEP |

|

| |

| |

| Contraindications for TDF/FTC as PrEP |

|

| |

|

PrEP:pre-exposure prophyaxis; TDF: Tenfovir disoproxil fumarate; FTC: Emtricitabine; STI:sexual transmited infection; ART: antiretroviral therapy

3.3. People who inject psychoactive substances

Thanks to the successful harm reduction programs, intravenous drug use is currently not a major risk for HIV in Switzerland anymore (20). We therefore recommend maintaining these well-established and accepted harm reduction strategies and not to implement PrEP within these programs in general. PrEP may be considered in groups of people who inject substances who until now are not reached by these programs yet, including, individuals, who use substances intravenously in a sexual setting or those who do not use sterile injecting material.

3.4. PrEP after HIV-post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP)

People, especially MSM, who have had an indication for PEP have been shown to have one of the highest risks for acquiring HIV (21). Information about PrEP should therefore be part of the consultation during PEP treatment. If the person decides to start PrEP following PEP, the approach on how to start PrEP can be challenging and depends on the estimated risk for future HIV exposures. In some cases, waiting the recommended six weeks to perform a fourth generation HIV test after completing a course of PEP might be too long as further HIV exposure may have occurred during that time. In these cases, two practical approaches can be considered. Either an HIV PCR test can be performed before PrEP is started after a shorter window period, or PrEP can be started immediately after completing PEP. If PrEP is initiated immediately after completion of PEP, the point of seroconversion and therefore the time at which any HIV antibody and/or antigen test is reliable is unclear. There is not enough data to determine whether PEP leads to false-negative PCR result in case of an HIV infection. Therefore, a PCR might help in the decision process but does not fully rule out HIV infection prior to PrEP initiation. In both situations – when the six weeks window period was not completed before PrEP was started – the limitations of the tests need to be discussed with the client and HIV screening tests need to be performed regularly during PrEP intake and when PrEP is discontinued. Table 2 can be used to help with these decisions. Consider contacting one of the SwissPrEPared physicians to discuss the individual case if needed.

Table 2: Considerations for future HIV risk in people who are prescribed PEP

| Estimated risk for future HIV risk situations | Practical examples | Clinical approach |

| low | Condoms are always used with non-steady regular or casual partners. The risk situation arose due to a technical problem (i.e. condom rolled off during sex) | PrEP start can be delayed until the standard final PEP consultation 6 weeks after PEP was completed, including a 4th generation HIV test. |

| medium | Condoms are not always used, for example due to insufficient protection strategies (e.g. ‘HIV-serosorting’) but the person can credibly confirm that they have no problems in using condoms in the six weeks after PEP treatment | Depending on the individual risk, consider performing an HIV PCR 21* days after PEP treatment before starting PrEP |

| high | Cases of inconsistent use of condoms, multiple prescriptions of PEP, sexualized use of stimulants (Chemsex), or mental health issues which lead to risk situations | Depending on the individual risk, consider starting PrEP directly after PEP. See the patient on a 4-weekly basis for HIV screening for the first 3–6 months. |

*There is not enough data on when a PCR is giving reliable results after PEP treatment.

So far, the combination of 245mg TDF and 200mg FTC is the only approved drug for PrEP in Switzerland. The following chapter refers to substances that cannot be prescribed for PrEP in Switzerland or can only be prescribed as off-label.

4.1. Tenofovir alafenamide (TAF)

Tenofovir alafenamide 25mg (TAF) and FTC has been studied among MSM and transgender women and has shown noninferiority when used on a daily regime (22). In 2019 it was approved in the United States (US) for PrEP in MSM, but until now not in the European Union or Switzerland. This combination can be considered for off-label prescription for people with a high risk of HIV infection and a risk of developing kidney damage. However, the US approval for TAF/FTC is officially only for people with a GFR > 60mL/min (www.fda.gov). Another barrier is the high price of this product in Switzerland. If a clinician thinks a person, who has a contraindication against TDF/FTC might benefit from TAF/FTC, we recommend getting in contact with a specialized PrEP center.

4.2. Lamivudine in combination with TDF

The World Health Organisation (WHO) considers lamivudine and emtricitabine as interchangeable in combination with TDF for HIV prevention (19). However, due to the lack of data for event-driven PrEP, we do not recommend this combination until further data is available.

4.3. Tenofovir alone

TDF alone has not been studied in MSM and is therefore not recommended for HIV prevention in Switzerland.

4.4. Cabotegravir

Eight-weekly intramuscular injections of the integrase inhibitor cabotegravir has shown to be superior to daily TDF/FTC in preventing HIV infections among MSM and transgender women (23) as well as among cisgender women (13). However currently real-life data is missing. In the US, cabotegravir has been approved for HIV prevention since December 2021. It has not yet been approved for PrEP in Switzerland. Off-label use is possible in theory, but high costs make is a less viable option.

4.5. Lenacapavir

Lenacapavir is a new HIV capsid inhibitor. Six-monthly subcutaneous injection of Lenacapavir showed significant lower HIV incidence in cisgender women, MSM and gender diverse persons compared to oral TDF/FTC and TAF/FTC (14)(24). The product is currently not available or approved for HIV prevention in Switzerland.

4.6. Dapivirin Vaginal ring (DVR)

The DVR is a silicone ring containing dapivirine, a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, delivered intravaginally for 28 days. In clinical trials, the DVR reduced the risk for HIV acquisition by 27–31% with no safety concerns or increased risk of HIV drug resistance (25)(26). DVR is available in 11 African countries, but not in Switzerland.

Studies with other drugs are ongoing and may lead to more alternative PrEP regimens in the future.

5.1. Start and Stop (Lead in/Lead out)

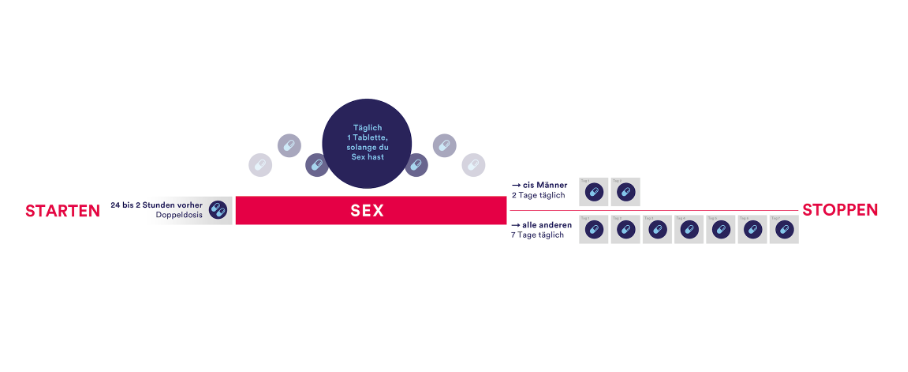

Whilst the first clinical trials used longer lead-in and lead-out phases of PrEP of 7 or even 28 days before and after a sexual risk, more evidence is available to support shorter lead-in lead-out phases. For cisgender men who have sex with men (MSM), a shorter lead-in and lead-out phase is feasible, as demonstrated by multiple studies following the IPERGAY protocol—also referred to as the “on-demand”, “event-driven” or “2-1-1” regime (5)(27). The IPERGAY study assessed PrEP with TDF/FTC given as two doses 2 to 24 hours before sex, one dose 24 hours after the first (double) dose, and one dose 24 hours later (‘2-1-1’ dosing). For consecutive sexual contacts, cisgender MSM were instructed to continue with one pill per day until two days after the last sexual encounter. With every new sexual encounter, PrEP was to be initiated with a double dose, unless the last PrEP dose had occurred within 7 days, in which case only one pre-exposure dose is recommended.

For cisgender women and other people who have receptive vaginal sex (including transgender men), longer lead-in and lead-out phase of 7 days due pharmacokinetic studies showing lower levels and a faster decay of tenofovir in the female genital tissue used to be recommended. However these studies actually show that protective levels of combined TDF/FTC were reached in 98% 2h after the oral intake of 2 pills of TDF/FTC (8). Regarding the optimal lead-out phase, the same study shows that the concentration was short-lived compared to colorectal tissue and therefore a 7 days lead-out phase should still be recommended to cisgender women and other people who have receptive vaginal sex. Many international guidelines therefore already include the new so called 2-7 regime for these populations. Although no clinical data exist on this regime so far, we still think evidence is good enough recommend this regimen for people who might otherwise choose no HIV protection at all. However, it is important that cisgender women and other people with receptive vaginal sex are made aware of this reduced level of evidence during the PrEP consultation.

Whilst there is a growing knowledge on the ideal start and stop time, some situations require special precautions:

Other regimens, such as continuous PrEP for four days a week (TTSS= Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday and Sunday) refer to retrospective data only and are therefore not recommended until further evidence is made available (studies still ongoing).

Figure 1: Lead-in/Lead out phases

5.2. Duration for PrEP intake

As the frequency of potential sexual exposure to HIV varies for each individual, different durations for the PrEP intake are used. Besides daily use, the most common regimen, some people with fewer sexual partners, prefer an event-driven regimen, where PrEP is only taken before and after a sexual contact.

An intermediate regime is the “Intermittent PrEP” or often called “holiday PrEP” where the PrEP is taken daily, but only over a limited period and with long intervals without PrEP.

Individuals asking for PrEP will be assessed at baseline visit (see the description below). For those deciding to start PrEP, a second visit is recommended four weeks after PrEP initiation to evaluate early side effects and to rule out acute HIV infection missed at baseline visit (HIV test window period). After the second visit, a 3-monthly plan is recommended for all individuals using daily PrEP, 3–6-monthly for individuals using PrEP not continuous, and a 6–12-monthly plan for individuals at risk of HIV who decided not to start PrEP.

Multiple studies are currently evaluating if a longer period between visits may be sufficient and more cost-effective. The frequency of STI testing is the subject of many discussions and ongoing research in the SwissPrEPared study. The Australian cohort has demonstrated, that a subset of PrEP users, namely 25% accounted for 76% of the STI diagnosis (30). While current studies struggle to present clear and accurate predictive risk factors to help guide professionals with which PrEP user is at high risk of STI and who is a lower risk, 3-monthly checks are still the standard of care for people using PrEP daily. However, 6-monthly visits seem acceptable if the PrEP user:

6.1. General recommendations for every visit

Besides the recommended laboratory tests, each visit should:

6.1.1. Screening for mental health and substance use

To combine evaluation of mental health problems with PrEP consultations has two advantages. Firstly, people at higher risk for HIV often belong to sexual and other minorities who are frequently exposed to stigmatization, discriminations and violence, putting them at higher risk for depression, drug addiction, and other mental health problems. Secondly, mental health problems, especially depression and addiction, have been shown to impair the adherence to PrEP. We therefore recommend evaluating people’s mental health at each PrEP visit, either in direct conversation or through a validated screening tool like the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4), which is used in the SwissPrEPared consultation tool.

6.1.2. Counselling on adherence

Adherence to medication is the most critical part of PrEP effectiveness. We therefore recommend to evaluate PrEP adherence at every visit and to support PrEP users who struggle with adherence. Several measures have shown to improve adherence:

6.2. Baseline visit

The following should be addressed at the baseline visit:

In case of a contraindication for PrEP, alternative HIV protection strategies should be discussed. If a person is already taking PrEP at baseline, the interventions will be adapted accordingly. If a person qualifies for PrEP but declines starting PrEP, a follow-up every 3 to 12 months is recommended to perform STI and HIV testing.

6.3. Safety-visit, 4 weeks after PrEP start

The following should be performed at a safety-visit:

6.4. Follow-up visits, 3 months after safety-visit and then every 3 months (can be extended to up to 6 months for non-daily PrEP use, depending on the individual risk)

The following should be performed every 12 months:

Table 4: Appointment schedule and key clinical assessments

| Baseline visit | Safety visit | Follow-up visit ( 3monthy in the first year, after that 3-6 monthly depending on risk) | Every 12 months | |

PrEP counselling, which includes:

| x | |||

| (Re-)Assessment of PrEP indication, regime and adherence | x | x | x | |

| Assessment of side effects, including interaction with existing medications or supplements | x | x | x | |

| Behavioural risk assessment | x | x | ||

| Symptoms of acute HIV infection (<1 month) | x | x | ||

| Adherence to medication and counselling | x | x | x | |

| Individual’s feedback on counselling | x | x | x | |

| HIV test | x | x | x | |

| STI screening (syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia) | x | x | ||

| Hepatitis C serology | x | x more often if specific risk behaviour is reported. See 6.4 | ||

| Hepatitis B Serology | x | |||

Assessment of vaccination status | x | |||

| Serum creatinine level, | x | x | x | |

| Protein/creatinine ratio | x | |||

| ALT | x | x | x more often, if elevated. see 8.3. |

PrEP= HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, STI= sexually transmitted infection, ALT= alanine transaminas

Regular STI checks were initially included in the PrEP consultation, with the hope to decrease the number of bacterial STIs over time on a population level based on mathematic modellings (31). Although data from the SwissPrEPared study suggest a certain success or this test-and-treat approach, no other study has been able to proof this concept in real life (32).

Different approaches were studied to reduce the number of bacterial STIs in this population. There was some optimism when retrospective studies suggested a cross-immunity in people who received the serogroup B outer membrane vesicle meningococcal vaccine (Bexsero®) with a 40% reduction in gonorrhea infections (33). However, a randomized trial showed a small reduction in gonorrhea cases of 22% which failed to reach statistical significance (34). Given these inconclusive results, we currently do not routinely recommend the off-label use of Bexsero® to prevent Gonorrhea in people using PrEP.

Multiple studies have shown a protective impact of 200mg of doxycycline given as post-exposure prophylaxis up to 72 hours after a sexual risk situation in MSM and trans women (34)(35). While the risk reduction was 70% or higher for chlamydia and syphilis in all studies, there was no clear benefit in the prevention of gonorrhea. Many guidelines therefore recommend the so called Doxy-PEP for MSM and trans women at risk for bacterial STIs (36). In San Francisco, where Doxy-PEP has been promoted since October 2022, a decrease of chlamydia and syphilis diagnosis is observed on a population level (37). Although Doxy-PEP seems to be the first intervention that has had an effect on lowering numbers of chlamydia and syphilis infections for decades, the impact of the wide spread use of doxycycline on antimicrobial resistance development and the microbiome remains unclear (38)(39). We encourage PrEP prescribers to openly speak with their clients about Doxy-PEP and address the unknown risks, especially as the prescription of doxycycline for prevention is currently off-label.

At the date of this publication, FCSTI is currently working on recommendations for Switzerland.

8.1. PrEP start-up Syndrome

The PrEP start-up syndrome describes a variety of gastrointestinal and non-gastrointestinal symptoms that may occur in the first days and weeks of PrEP initiation. They are usually not associated with target organ damage, and are self-limiting after a few days until a maximum of 8 weeks (40).

Side effects can include nausea, flatulence, abdominal pain, dizziness, and headache. These symptoms occur early, but usually disappear within the first month. They can often be managed with a symptomatic treatment like analgesia or anti-emetics, if necessary.

8.2. Alterations in kidney function due to TDF and recommended surveillance

TDF is known to induce proximal renal tubulopathy (PRT), known as Fanconi syndrome, in some individuals (41). This is a very rare side effect where the proximal renal tubules do not absorb certain electrolytes and amino acids, resulting in a loss in the urine. Proteinuria, hypophosphatemia, hypokalemia, hypouricemia, renal acidosis and glucosuria, with normal blood glucose level, are characteristic of PRT as well as possible renal insufficiency and polyuria. In PRT, it is possible that despite the presence of proteinuria and hypophosphatemia, the creatinine clearance remains within the normal range. Most often, only some of these abnormalities are observed, and it is not certain which tests discriminate best for TDF renal toxicity.

8.2.1. Frequency of kidney function testing

After starting to take TDF for PrEP, a small but statistically significant decrease in creatinine clearance may be seen from baseline, which resolves after stopping TDF/FTC (42). There are no data for people with eGFR<60 mL/min, so continuing TDF/FTC if eGFR falls to below 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 is not advised.

Reduction in creatinine clearance while taking TDF/FTC alone is a rare side effect and many international guidelines now recommend checking the kidney function in healthy PrEP clients with no other risks for kidney failure only once or twice a year (43)(44). Although 6–12-monthly tests might be sufficient for people without risk factors, we recommend routine checking of kidney function at every visit for people considered at greater risk, for example, people with:

8.2.2. How to screen for kidney function

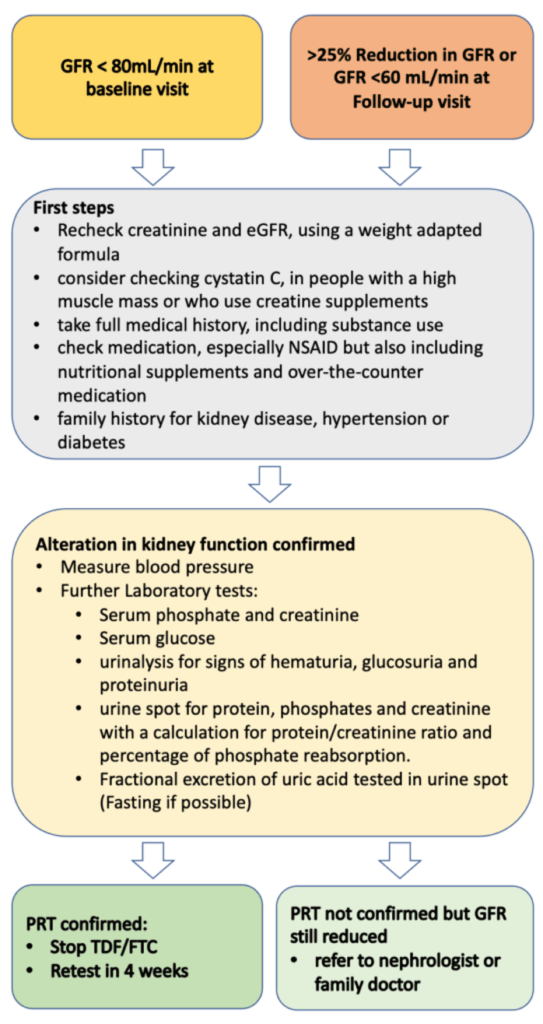

8.2.3. Stepwise approach in case of reduced GFR

In case of an alteration in kidney function, we recommend a stepwise approach (fig.3)

If a decrease in the GFR is confirmed, we recommend the following further investigations:

If laboratory tests confirm PRT, stop TDF/FTC and test kidney function again after 4 weeks. A change from a TDF to a TAF-based PrEP regimen can be considered (29). However, TAF is not currently authorized by Swissmedic for prevention in Switzerland, and there are no generic versions available in Swiss pharmacies. Formally, the FDA label is only for people with a GFR >60 mL/min.

If lab results do not confirm PRT, still consider stopping PrEP, especially if GFR is <60 and refer the client to a kidney specialist.

Figure 3: Stepwise approach in case of alteration in kidney function

GFR= Glomerular filtration rate, NSAID= nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, PRT= proximal renal tubulopathy, TDF= Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, FTC= Emtricitabine

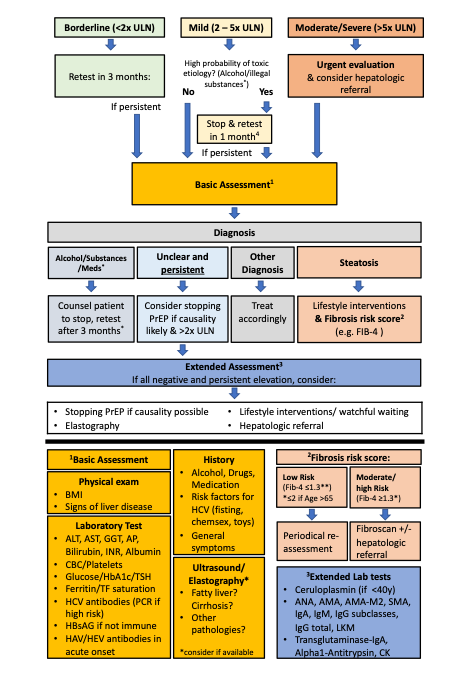

8.3. Increase in levels of liver enzymes

TDF can cause a mild to moderate increases in liver alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in some people living with HIV (45) and in some PrEP users (46). The clinical relevance of these findings is unclear, and most guidelines do not recommend including ALT tests in regular PrEP visits (43)(44). To our current knowledge, cases of severe PrEP induced liver injury have not been reported. As mild elevation of liver enzymes is common in the general population (prevalence estimates mostly >10%) (47), elevation of liver enzymes in PrEP clients is likely to have other origins than TDF induced liver toxicity, e.g. alcoholic liver disease (ALD), non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Liver toxicity due to recreational drug use and viral hepatitis might be more common in PrEP clients than in the general population.

The benefits (early detection of disease and potential drug toxicity) and risks (overdiagnosis, stopping PrEP unnecessarily, complications of further examinations, costs) of screening in PrEP clients are unclear, and evidence informing a recommendation is lacking. Furthermore, the upper limit of normal (ULN) for transaminases is disputed. Values in the normal range do not exclude liver diseases (48), and subsequent diagnostic evaluation of mildly elevated transaminases often do not find specific liver diseases (34). By taking into consideration that PrEP is prescribed to healthy clients as prevention, we recommend testing for ALT before starting PrEP, at the safety visit and every 12 months thereafter, until more data on liver toxicity is available.

If elevated liver enzymes are observed, other reasons than PrEP intake should be considered. For non-acute and asymptomatic patients, we propose a stepwise approach detailed in the algorithm below (fig.4), which we developed in adaptation to the EACS guidelines (3). When a persistent or significant ALT-elevation (>2x ULN) is observed, a basic assessment of the most common liver pathologies should be conducted. In the basic assessment, toxicity due to other medication and substances (e.g., anabolic steroids, cocaine, ecstasy), ALD, NASH, hemochromatosis, viral hepatitis and symptoms indicative of systemic diseases involving the liver should be evaluated. Individuals should be evaluated for liver steatosis with ultrasound and, if present, a fibrosis risk assessment using an established score conducted (e.g., Fib-4) (48). A low-risk score allows for periodical reassessment. For moderate results preforming transient elastography and for high-risk scores, a hepatologist referral is recommended (3)(48). If available, a transient elastography might be considered in the basic evaluation, but in most guidelines, ultrasound is recommended as the primary first screening tool for NAFLD (3)(48)(49)

If no cause can be identified, and the elevation of liver enzymes persists, rare causes (autoimmune liver and metabolic liver diseases) should be evaluated. Furthermore, stopping PrEP and a hepatologist referral should be considered. For significantly elevated liver enzymes (≥ 5.0 x ULN), acute onset and/or symptomatic patients, the proposed algorithm should be used with caution and a timely, comprehensive evaluation and hepatologic referral should be evaluated. It is important to emphasize that the finding of liver steatosis might have multiple origins. If, despite lifestyle interventions, the ALT-elevation progresses or fibrosis develops, other causes should be considered.

Figure 4: Stepwise approach for elevated ALT

4 Alcohol and substance use leading to elevated liver enzymes is often caused by a problematic use or addiction which cannot be easily stopped. Counsel to stop and retest after 1 month is often insufficient in such situations. Consider referral to addiction medicine

ULN=Upper Limit of Normal, PrEP=Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, BMI=Body-Mass-Index, ALAT=Alanin-Aminotransferase, ASAT=Aspartate-Aminotransferase, GGT=Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase AP=Alkaline Phosphatase, INR= International Normalized Ratio, CBC=Complete Blood Count, HbA1c= Glycated Hemoglobin, TSH=Thyroid Stimulating Hormone, TF=Transferrin, HCV= Hepatitis C Virus, HbsAG= Hepatitis B Antigen S HAV= Hepatitis A Virus, HEV= Hepatitis E Virus IgA Immunoglobulin A, IgM= Immunoglobulin M, IgG= Immunoglobulin G, LKM= Anti–Liver-Kidney Microsomal Antibody, CK= Creatine Kinase

8.4. Decrease in bone mineral density (BMD)

The use of TDF in people living with HIV is associated with an early decrease of 3-4% of bone mineral density after treatment start, especially when co-administered with a boosted protease inhibitor (50). In HIV-uninfected individuals using TDF/FTC as PrEP, this effect seems to be less pronounced (~1%) without increased fracture risk (42)(51)(51)(52). No routine screening with bone densitometry is necessary for individuals using PrEP. Increased physical activity, smoking cessation, and reduction in alcohol consumption may reduce the long-term fracture risk in all individuals, and calcium supplementation may be considered if intake is insufficient. The ten-year fracture risk should be assessed in individuals with risk factors for osteoporosis (e.g., history of falls or fracture, use of glucocorticoids) using the FRAX score, and bone densitometry should be performed in those with a high fracture risk to further assess the need for treatment. As the clinical consequences of the bone density reductions associated with PrEP remain unclear, the decision if TDF/FTC based PrEP should be prescribed in the presence of osteoporosis depends on the individual’s risk for HIV infection. For person’s with less sexual risks, switching from a daily to an event-driven regime to reduce TDF exposure might be beneficial to reduce the risk of a further reduction in bone density.